The problem of water resources management in the Kathmandu Valley is multi-faceted and complex. Problem areas include (lack of) regulations on chemical discharge, sewage treatment, land encroachment, among others. Nevertheless, if we set the right goals and challenge on defining this problem, we can build feasible long term framework to solve it. The problem will only increase in scale in the coming decades due to urban growth.

If we want to do it right we have to plan for a solution that works for many decades to centuries.

If we want to do it right we have to plan for a solution that works for many decades to centuries.

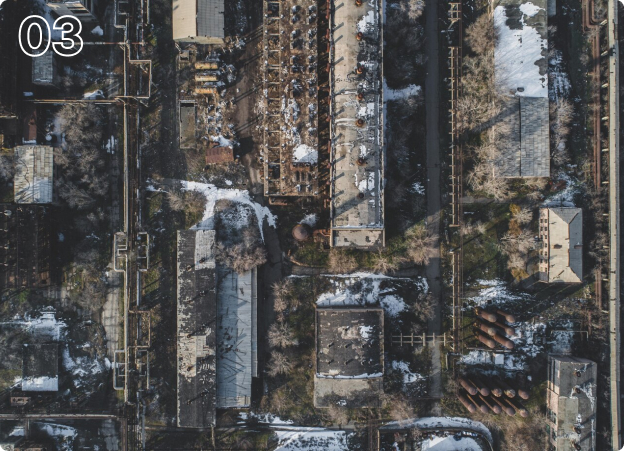

Covering roughly 721 square kilometers, the Kathmandu Valley is a bowl-shaped valley at the foothills of the Himalayas. The valley is located between 27°49′4″ and 27°31′42″ latitude and 85°11′19″ and 85°33′57″ longitude, and it consists of approximately half of Lalitpur district and the entirety of Kathmandu and Bhaktapur districts. According to the 2021 census, Nepal has a population of 29 million, of which roughly 3 million people inhabit the Kathmandu Valley itself. With the city of Kathmandu serving as the capital of Nepal, the Valley has witnessed urbanization at a rapid pace. A report published in 2020 estimated that the Valley was witnessing growth at an annual rate of 6.5%.

At this rate the population of the Kathmandu Valley will double every 10 years.

If population growth plateaus after 2050, a solution geared for 8x to 10x current population should last centuries. As monsoon patterns change due to global climate change, the plan needs to take into account these changes.

The latest census found that the urban population of Nepal increased from 63.2% in 2011 to 66.8% in 2021. The urban population density of Kathmandu Valley is 3,365 persons per square kilometer, while it is 5,108 individuals per square kilometer for the capital city. As more and more people move to urban areas in search of better jobs, facilities, and opportunities for education, the strain on existing infrastructure and natural resources is only growing.

The Bagmati River, which emerges from the Shivapuri hills at a height of 2,650 meters, is a lifeline for the Kathmandu Valley. Joined by its tributaries, the Bagmati flows through Nepal before finally entering India. In Nepal, the waters of the Bagmati are considered sacred by the Hindu and Buddhist communities. While it serves as the final resting place for Hindus, who are cremated on its banks, the Kirati people are buried in the hilly areas nearby.

At this rate the population of the Kathmandu Valley will double every 10 years.

Unfortunately, the holiest river of Nepal is also its dirtiest. As it makes its way through the Valley, its waters are pristine and clear near the source but begin turning dark and murky near the organized areas — and black by the time it reaches the capital city. With water that is considered too dirty to drink, or even to use for cleaning, even after-death rituals are now conducted with bottled water.

The residents of Kathmandu Valley find it difficult to access clean, safe drinking water. The Valley has witnessed numerous outbreaks of cholera, believed to be linked to the presence of traces of human and animal waste in drinking water. Most people use sources of groundwater for their drinking, cooking, and cleaning needs. Unfortunately, studies have found that even groundwater in the Valley is contaminated with dangerous chemicals, like arsenic and manganese, as well as pathogenic microbes. Further research has proven that bathing in the river can increase the risk of contracting diseases like paratyphoid fever, cholera, and dysentery, among others.

Unfortunately, the holiest river of Nepal is also its dirtiest. As it makes its way through the Valley, its waters are pristine and clear near the source but begin turning dark and murky near the organized areas — and black by the time it reaches the capital city. With water that is considered too dirty to drink, or even to use for cleaning, even after-death rituals are now conducted with bottled water.

The residents of Kathmandu Valley find it difficult to access clean, safe drinking water. The Valley has witnessed numerous outbreaks of cholera, believed to be linked to the presence of traces of human and animal waste in drinking water. Most people use sources of groundwater for their drinking, cooking, and cleaning needs. Unfortunately, studies have found that even groundwater in the Valley is contaminated with dangerous chemicals, like arsenic and manganese, as well as pathogenic microbes. Further research has proven that bathing in the river can increase the risk of contracting diseases like paratyphoid fever, cholera, and dysentery, among others.

In addition to human and animal waste, large quantities of industrial waste are dumped daily into the Bagmati River and its tributaries. Industrial waste from factories and hospitals has been blamed for the high levels of Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) and low levels of DO (Dissolved Oxygen) in the river. The BOD value of polluted water falls between 6 to 9 parts per million (ppm). However, the BOD level of river water that had passed Chobhar, the exit point of the Bagmati River from the Valley, was recorded at 340 ppm during the dry season of 2023. Here, it is important to remember that water bodies with high BOD levels and low DO levels are not conducive to supporting aquatic life. Numerous cases of mass fish deaths around the world have been blamed on low levels of Dissolved Oxygen in the water.

As the Bagmati nears the capital city, the levels of grease and oil surpass the upper limit set by the World Health Organization (WHO) for safe drinking and cooking water by at least ten times. These unsafe levels have been blamed on the many car and garage service shops located nearby. Even the levels of ammonia were found to be high at numerous points of the Valley — at least 100 times the safe limit prescribed by WHO. In Thapathali, which is roughly 3 kilometers from the Kathmandu city center, the waters are especially polluted. Binod Baniya, Nitesh Khadka, Shravan Kumar Ghimire, Hom Baniya, Shankar

Sharma, Yam Prasad Dhital, Ranjana Bhatta, and Bishnu Bhattarai in Water quality assessment along the segments of Bagmati River in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal found that the level of arsenic was 65 times the safe limit prescribed by WHO. The high level of arsenic, which can lead to cancer, diabetes, heart problems, and even impaired development among children, in the waters near Thapathali has been linked to the presence of two hospitals in the area. Furthermore, the United States Environmental Protection Agency maintains that the presence of Heptachlor epoxide, a pesticide, should not exceed 0.0002 mg/L. Shockingly enough, the research found that the presence of this toxic chemical was found at 345 times the safe limit in the waters near Thapathali and 375 times the safe limit in nearby Balkhu.

In simplistic terms, adequate sewage treatment infrastructure and a lack of regulations are to blame for the deteriorating water quality of the Bagmati River once it enters the Kathmandu Valley. But that is not all: Even a banned activity, like sand mining, continues to be rampant in the Valley.

It was a bridge collapse in 1991 that finally led to the ban on sand mining, but reports claim that illegal sand mining continues to threaten the ecosystem of the Bagmati. Sand mining is banned for a number of reasons: Not only does it threaten the foundation of homes, bridges, and other infrastructure, but it also increases the risks of flooding. In addition to this, extracting sand from the river bed can deepen the water table and influence the migration of aquatic animals. It can also reduce the availability of drinking water, as a lower water table makes it harder to extract water from wells.

Sand mining and land encroachment near the riverbed have been blamed for increased instances of flash floods in the Valley. Unchecked urbanization, such as in the Valley, can alter the courses of rivers, making them narrower and impacting their ability to hold excess water. Unfortunately, this is not all: Construction materials like concrete have replaced soil in many areas near the river bank. This means there is less soil available to absorb the excess rainwater. Flood Risk Modeling in Southern Bagmati Corridor, Nepal by Bitu Babu Shreevastav, Krishna Raj Tiwari, Ram Asheshwar Mandal, and Bikram Singh found that areas with dense construction were more prone to flooding. The same study observed that high drainage density (the cumulative length of all the streams within a drainage basin divided by the area of that basin) means there is a lower chance of flooding.

It is pertinent to note that the drainage infrastructure in the Valley was set up decades ago and is not considered capable of dealing with the monsoon rains. Kumar Chaudhary, R., Kumar Mishra, R., & Jha, P. (2023) in ‘Navigating flashfloods in Kathmandu Valley: Strategies and policy reforms’ Water Science highlight another issue: When the streams are overflowing with flood water, their water level becomes higher than the level of the stormwater drains in Kathmandu Valley. This causes water to flow towards residential areas.

While the water is unsafe for consumption and swimming among locals, it has already decimated the river ecosystem. As it nears the urbanized areas of the Valley, the Bagmati becomes biologically dead. This means its waters cannot support aquatic life, like aquatic animals and plants, anymore. High levels of toxic chemical waste, low levels of Dissolved Oxygen, and altered river beds are typically the reason for rivers being unable to support life.

For the biologically dead Bagmati River, there is still hope. Through sustained efforts, rivers around the world have been brought back to life — the River Thames in London, the Kuttamperoor River in south India, the River Seine in Paris, and the Yongding River in Beijing are just some examples.

Paris to bring back swimming in Seine after 100 years.

— BBC News, 2024-July-24

A Detailed examination of the factors contributing to the Bagmati River’s pollution and how they affect the invironment and public Health.

Despite its critical state, successful urban river restoration projects offer hope:

Although the Bagmati River is biologically dead today, restoration is possible through long-term policies, sewage treatment improvements, and community conservation efforts. Inspired by cities like Paris and London, where rivers have been revived, a cleaner Bagmati can once again become a source of life, beauty, and cultural heritage for future generations.