Any large-scale project requires an analysis of various factors, as these have the potential to determine its outcome. While factors such as cost and time required for completion are important for any task, the restoration of a river is a complex socio-technical project that entails taking into account several other factors.

To streamline our presentation and simplify the evaluation process, we have grouped these parameters into three categories:

| Input Factors | Process Factors | Output Factors | Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost and Funding model | Time required | Measurable physical metrics (Biological Oxygen Demand, Drinking water supply capacity) | Climate change and Environmental |

| Community involvement and potential impact | Gradual improvement vs Big Bang impact | Potential revenue | Technical Implementation Risk |

| Political appetite | Kind of technology required | Integration with other multi-objective projects | Cost risks |

| Availability of local expertise | Maintenance and Sustainability | ||

| Measurement and Reporting |

Please note that these categories are not mutually exclusive. For instance, cost can be considered as both an input factor and a process factor. This categorization is done to aid visualization and structure the assessment process.

An early estimate of the cost is required to understand the feasibility of the project. However, any such estimate can be tricky to validate as it would need to account for the complexity of the project, local economic situation, and benchmarking of similar river rejuvenation projects, among other factors.

Successful river cleanup projects have generally been expensive: Costs for the Thames Tideway Tunnel reached £5 billion (over US$6 billion), which was higher than initial estimates, while Europe’s Rhine River was restored at a cost exceeding €50 billion (nearly US$54 billion) over three decades.

Closer to home, India has spent INR 328 billion (over US$3.9 billion) on its ongoing Namami Gange mission to clean the sacred River Ganga. The project is expected to incur further costs.

Nepal is an emerging nation, with a nominal GDP of US$40.83 billion in 2022. As a developing country, Nepal has fewer resources than its European counterparts. However, high costs can be offset by using local human and material resources in the planning and execution process, using local and available infrastructure or materials, and exploring opportunities for revenue generation. We are looking for innovative solutions that are affordable for Nepal.

The annual budget of the Kathmandu Metropolitan City was US$190 million in 2024/2025.

Just for exemplification, let us assume that the budget for the proposed projects and programs will be US$10 billion. If only 10% of the city budget is used for the project, the project will take 100s of years of funding. On the other hand, if the federal government pitches in, and there is funding from civic donations, it could be feasible at a shorter time frame.

For example, there were around 5 million Non-Resident-Nepalis in 2018. If 50% of these Nepalis donate US$1 per day, the funding for a US$10 billion project could be funded in about a decade.

We are providing some benchmarks here to compare with other projects around the world for teams looking to propose solutions to think big and in realistic terms. However, this is not a target. Teams can propose solutions that have estimates of any cost point. If there is a way to generate revenue and reduce the total budget, it could rank given proposals favorably in this framework.

Funding models are technically separate from the cost, but we encourage teams thinking about solutions to think about the funding model in addition to the cost required for the proposed project.

How can a mammoth, expensive project secure funding? World over, projects have secured funding through traditional and out-of-the-box methods.

For instance, the cost of the Thames Tideway Tunnel is being borne by the customers of Thames Water, the company in charge of building the tunnel. Thames Water has about 15 million customers, who will be paying off the extra costs over the next few decades. The company has said that their bills will not increase by anything over £25 annually.

Meanwhile, the cleanup of the Rhine River was funded by several European countries that are part of the International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR). It proved that international cooperation can go a long way in improving the lives of millions of people.

Public-Private Partnership: Traditional funding methods include the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) model, wherein a government or state agency partners with a private entity to complete a public infrastructure project. This type of agreement could include tax incentives and an opportunity for revenue generation for the company. India’s ambitious project to clean the Ganga River adopts a hybrid-annuity PPP model, wherein private companies were awarded tenders to build sewage treatment projects. What differentiates this from a traditional PPP model is that the government is bearing up to 40% of the capital expenditure and paying the rest in annuity payments. This provides an incentive for the project to reach completion.

Government grants: A government grant can be secured via national or state governments. The beneficiary of the grant is not expected to repay the amount, but instead, is expected to use it to complete the given project. Last year, the government of Ireland awarded 142 grants exceeding €520,000 ($560,000) in an endeavor to empower citizens to restore riverine ecosystems and water bodies.

Green bonds: A green bond is issued only to fund sustainable, climate-friendly projects. There are a number of international agencies that release green bonds. An example would be the World Bank, which has released green bonds worth $19 billion for climate-friendly projects, like watershed management, since 2008. Another example is the District of Columbia Water and Sewer Authority (DC Water), which released its green bonds in 2014 to restore the riverine ecosystem and improve sewage management as part of the Clean Rivers project.

International aid and development loans: Foreign aid can be secured via development banks and financial institutions. For instance, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has partially financed the Bagmati River Basin Improvement Project. This project, which aims to beautify a stretch of the river and install a flood warning system, has received $93 million in funding from ADB.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR): Businesses may choose to allocate their CSR budget towards environment-friendly initiatives. In India, businesses can help fund projects like waste management and river cleanup through the Clean Ganga Fund.

Any large-scale project has the potential to impact local communities. Such an impact could include displacement, loss of livelihoods, and even bad media publicity. The Narmada Bachao Andolan, a 20th century agitation in India, had been launched to protest the inadequate rehabilitation of thousands of tribals and farmers who would have been displaced due to a project to build dams across the Narmada River.

However, several international projects have made efforts to engage local communities and share the benefits of the project. This has included awareness programs, involvement in decision making, and even the creation of jobs.

India’s Namami Gange program to clean River Ganga involves the creation of nearly 4,500 ‘self-sustaining model villages’ along the route of the river. The program also includes the installation of sanitation facilities and boosting tourism and traditional craftsmanship as part of brand ‘Ganga’.

The Elizabeth Line, earlier called Crossrail, is another example of such a project. Professor SN Pollalis and researcher D. Lappas, in their February 2019 study titled Crossrail -Elizabeth Line, London, UK, noted that when the rail line was being built, it created 55,000 employment opportunities across the United Kingdom. The Crossrail also made efforts to minimize environmental impact, with almost all of the soil that was dug out to construct the line being used in the construction of wetlands and even a bird sanctuary. In addition to this, Crossrail also established channels to address complaints raised by the public in a timely manner.

Considering the impact that a large-scale project can have on the communities living nearby, any project to clean the Bagmati River should strive to involve the local community, consult with all the stakeholders, create job opportunities for the local population, and minimize adverse impacts.

Proposals shall also be evaluated based on a ranking on how risky the proposal is. There could be various dimensions along with risk is analyzed. We list some possibilities below.

Cost Overrun: There is always a possibility of a major infrastructure project exceeding its budget. In addition to miscalculating the amount of resources required, unexpected hikes in material and labor costs can lead to significant cost escalations. Furthermore, a long-term project may require continuous funding. The future of long-term projects that are reliant on aid organizations or government funding is vulnerable, especially if the leadership or government changes.

Britain’s Hinkley Point C nuclear power plant has encountered multiple setbacks and spiraling costs, triggered by rising construction expenses, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the uncertainty caused by the Ukraine war. Once envisaged as costing £18 billion (over $22.5 billion), the cost to build the nuclear reactor could climb to £46 billion (nearly $57.6 billion) if inflation is considered. The project is not likely to finish before 2031, nearly 15 years after its original completion date.

Project Delays: From weather conditions and labor strikes to delayed permits, infrastructure projects can face delays due to a number of reasons. Even a transfer in political leadership can delay the completion of a major project — What may have been a priority for one government may not be for another.

India’s latest effort to clean the River Ganga is not its first, although it is probably the most extensive. Before the Namami Gange program came into being in 2014, the Ganga Action Plan (GAP) was being implemented. Launched in 1986 in an effort to restore the holy river, it was riddled with allegations of mishandling and corruption. The project was eventually abandoned.

Safety Hazards: To prevent injuries and casualties among workers and other citizens, all infrastructure projects must follow the required safety protocols. Therefore, project managers should strive to use quality materials during every step of the process and ensure that all safety protocols are duly followed. Failure to do so can be inconveniencing at best and catastrophic at worst.

In 2017, the Oroville Dam in California came close to flooding, forcing evacuations of hundreds of thousands of people amid fears of the spillway collapsing. It later emerged that several environmental organizations had raised fears of safety risks within the dam over a decade before the incident took place. An independent team, comprising John W. France, Irfan A. Alvi, Dr Peter A. Dickson, Dr. Henry T. Falvey, Stephen J. Rigbey, and John Trojanowski, found in the Independent Forensic Team Report, Oroville Dam Spillway Incident, dating January 2018, that the state of the foundation underneath the spillway was substandard and repeated site inspections had failed to notice its deteriorating condition.

It is pertinent to note that while there will always be some risks associated with a major project, many of these can be anticipated and prevented during the planning process itself. Every effort should be made for the project to meet its goals, and this means evaluating all steps and associated risks from start to end.

Resilience to Climate Change and Environmental Risks: Resilience to climate change and environmental risks in water resources management projects is crucial for sustainable development. Around the world, innovative strategies are being implemented to enhance this resilience. In the Netherlands, the Room for the River programme exemplifies adaptive management by redesigning river landscapes to accommodate higher water levels, reducing flood risks. In Australia, the Murray-Darling Basin Plan focuses on integrated water management, balancing environmental, agricultural, and community needs while adapting to variable climate patterns. In Kenya, the use of rainwater harvesting and storage systems in arid and semi-arid regions provides a buffer against droughts, ensuring water availability during dry periods. These examples highlight the importance of flexible, context-specific approaches in building resilient water systems capable of withstanding the impacts of climate change and environmental uncertainties.

Nominal Time Estimate: The time it takes to restore a river to its original state depends on the method, scale and ambition of the restoration project. A highly polluted river is likely to require continuous and extensive restoration work for years, and possibly even decades, while a smaller river that requires only certain actions could be cleaned in as little as a year.

The Kuttamperoor river in southern India is one such example. The river had suffered at the hands of land encroachments, sewage dumping, and sand mining, and its width had narrowed from 100 meters to barely 10-15 meters. However, a six-year-long effort by locals, the state government, and even some landowners, managed to restore the river and bring back its aquatic life. While the locals cleaned the river, many landowners donated private land so the river could flow again.

In contrast, the River Thames in London took much longer. It was recognized as one of the cleanest urban rivers over six decades after being declared biologically dead. Here, it is pertinent to note that the Thames underwent a gradual cleanup process involving the construction of sewers, passing of legislation, and even deployment of oxygenators.

Gradual Improvement vs. Big Bang Approach: With public funds being utilized to clean the Thames, it was imperative for the restoration plan to work. A gradual approach, starting with sewage treatment and legislation, before progressing to oxygenators, allowed authorities to take action and judge their impact. This method allows for more flexibility: The authorities and stakeholders involved can always test whether their approach is working, and if not, devise other strategies.

In contrast, fast-paced improvement helps make significant advances in a short span of time. But this approach comes with its own set of risks: River restoration projects are generally very expensive and resource-consuming. If they are fast-paced, they might not leave any time even to check preliminary results and adjust strategies if required.

The outcome of a project depends on its planning and execution, which is why fast-paced approaches should have undergone a meticulous planning process and risk assessment. It is imperative to note, however, that a fast-paced approach may not always be unsuccessful. For instance, in 2018, the Indonesian government launched a drive to clean the highly polluted Citarum River in West Java within a span of seven years. The water quality of the river is believed to have improved, with fishing resuming and the water reportedly safe to swim in some places.

A gradual improvement approach verses a big-bang approach is likely to reduce risks, but it can mean longer development total development time.

In any developing country, the use of locally available technology can have a positive impact on the costs and timeline of the project. Using the expertise of government entities and private players can encourage participation and promote economic growth. India’s drive to clean the River Ganga includes the National Remote Sensing Centre (NRSC), which is a part of the country’s space organization, employing geospatial technology for a number of tasks including the monitoring of water pollution.

However, there may be times when a country needs the technology required to produce the desired results. If this particular kind of technology is produced elsewhere in the world, then it could be beneficial to call in experts from that country. For instance, the Japanese government has partnered with its Indonesian counterpart to share expertise and technology on industrial waste treatment and mercury waste management in the Citarum River. Most countries will opt for a mix of local and imported technology: India, for example, had wanted international agencies to exhibit their technology for the ‘in-situ bioremediation’ of wastewater and had extended an invitation in this regard.

The Arvari River stems from the Aravalli Hills of Rajasthan — the driest state of India. While it currently flows through the district of Alwar, this was not always the case. For roughly six decades, the Arvari had dried up.

Dubbed the ‘Waterman of India’, Dr Rajendra Singh led a team of villagers to build johads, a traditional earthen dam that collects rainwater. The rainwater collected in the johads percolated underground, feeding the river basin. The river started flowing in 1990, about four years after the rainwater harvesting began.

In addition to involving villagers, river restoration projects can also seek the help and expertise of local authorities. Not only can local authorities encourage participation and innovation among the villagers, but they also have a better understanding of community needs, strengths, and expertise.

While any large-scale project cannot solely depend on local expertise and may need national or international assistance, an ideal solution would involve a mix of using local knowledge and leveraging guidance from other experts.

Measurement and reporting in water resources management projects are essential for ensuring transparency, accountability, and informed decision-making. Globally, various frameworks and technologies are employed to monitor and report on water usage and quality. In the United States, the National Water Quality Monitoring Council utilizes a network of sensors and data collection stations to provide real-time water quality data, enabling swift response to contamination events. In India, the Jal Jeevan Mission employs a centralized digital dashboard to track the progress of water supply projects, ensuring that targets for rural water access are met. Similarly, the European Union’s Water Framework Directive mandates comprehensive monitoring and reporting by member states, promoting sustainable water management practices across the region. These examples underscore the significance of robust measurement and reporting systems in managing water resources effectively, fostering a culture of transparency and continuous improvement.

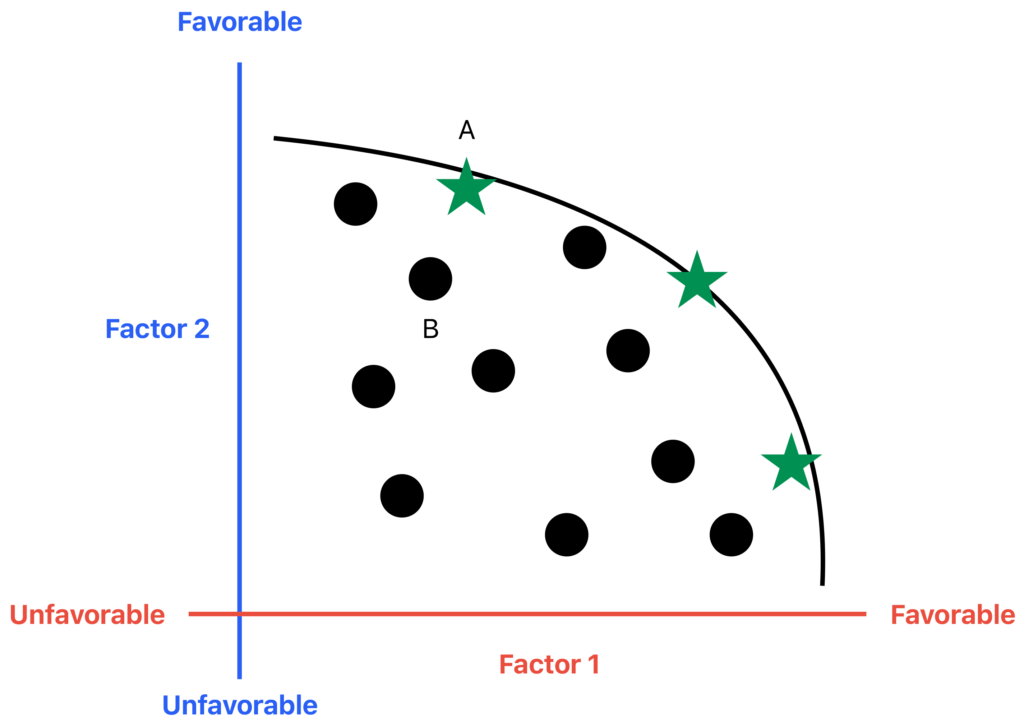

A co-author of this framework was part of the team researching multi-disciplinary teamwork, and its relationship to systems thinking at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the Global Teamwork Lab under the MIT System Design and Management program. A salient point that we learned from this research is that having an idea of the space of potentially conflicting objectives allows teams to explore. Plotting solutions under this space is an approach that allows teams to explore and compare ideas more easily and get to a better solution. Here we provide a framework to frame the problem so that the full problem and solution spaces can be explored more effectively.

When multiple factors are considered, there can be situations where a solution needs to trade-off favorability on one factor vs. another. However, there can also be solutions that are worse off in many of the factors considered. When there are only 2 factors, this can be illustrated as in the diagram above where solution A (and other solutions indicated with a star) are strictly better than, for example the solution B. This concept is called the Pareto frontier. Assuming we can correctly evaluate a given solution, assessing the solutions in terms of a Pareto frontier is a good way to compare solutions systematically.

Hello! We invite you to be part of the mission to restore the Bagmati River to its natural state. This is your chance to submit innovative solutions that address the river’s environmental challenges. Check out the criteria and share your vision for a cleaner, greener future. Together, we can make a difference!

These cover the investments and resources necessary at the beginning of the project:

An early cost estimate assesses feasibility. Given the high costs of similar global projects, the Nepal project must align with local economics. Funding could include public, private, and international contributions.

Engaging local communities is essential to prevent adverse effects such as displacement or loss of livelihoods. Involving them in decision-making and job creation is critical for successful outcomes, as seen in India’s Namami Gange program.

Political will and government support are crucial for the success and longevity of such a large-scale project.

These cover the investments and resources necessary at the beginning of the project:

Project timelines can vary significantly based on scale and approach. Large, polluted rivers may require gradual, long-term efforts, while smaller rivers may see faster results

Decisions around technology—whether local or imported—impact cost, timeline, and sustainability. Projects like India’s Ganga rejuvenation use a blend of local and international expertise.

Efficient management of the project will ensure that costs stay within budget, timelines are met, and the impact is as intended.

These cover the investments and resources necessary at the beginning of the project:

Metrics like Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD) and drinking water supply capacity are crucial for evaluating the success of water quality improvement

The project could generate revenue through tourism, local business growth, or other means, reducing reliance on public funding.

The primary goal is to restore the river to a healthier state, which can improve public health and ecological sustainability.

These cover the investments and resources necessary at the beginning of the project:

Long-term resilience to climate change must be considered, particularly in areas prone to flooding, drought, or other environmental challenges.

Ensuring the safety of workers and citizens is essential, especially in large-scale infrastructure projects.

A critical part of any large-scale project is securing adequate funding, which can be sourced through

Collaborations between the government and private companies, which can share both the financial burden and the potential profits.

Grants can be used to support the project without expecting repayment

Issuing bonds for environmentally sustainable projects can attract investment for projects like river cleanup.

Securing loans or aid from development banks or international institutions to finance the project.

Companies may allocate part of their CSR funds for environmental projects.

Issuing bonds for environmentally sustainable projects can attract investment for projects like river cleanup.

Hello! We invite you to be part of the mission to restore the Bagmati River to its natural state. This is your chance to submit innovative solutions that address the river’s environmental challenges. Check out the criteria and share your vision for a cleaner, greener future. Together, we can make a difference!